Justice Mukheli’s story begins in Soweto, where the streets were alive with graffiti, skating, and the restless and vibrant energy of youth

Mukheli is a revered photographer and filmmaker whose work spans multiple mediums and genres. He has directed poignant short films for platforms such as TikTok, as well as family-centred commercial projects. From his early artistic pursuits as a child growing up in Soweto to establishing himself as a respected photographer and advertising art director, Mukheli has consistently used his creativity to tell stories that simultaneously challenge and emphasise the narrative of the black experience.

Growing up in Pimville Zone Four, he found himself drawn not only to soccer or the conventional pastimes of his peers, but to the colourful rebellion of graffiti that has inspired generations. The trains he travelled to school with became moving galleries, walls became canvases, and spray cans, another language of defiance in a place where so many cultures melded. With his twin brother and formidable multidisciplinary artist, Fhatuwani Mukheli, and friends, he formed a graffiti crew, sketching, painting, and immersing himself in a culture that gave him identity and refuge. Mukheli muses on those days lovingly,

“We were a young crew of graffiti artists who skated and drew. We spent time sketching, buying books, reading magazines, and visiting internet cafés or libraries to find graffiti materials and watch graffiti films.

Graffiti and skating were more than art and adventure; they were each a gateway. Through his varied interests and hobbies, Mukheli met mentors like Back to City Festival Founder, Osmic Menoe, who introduced him to advertising and art direction. From there, his journey expanded into photography, filmmaking, and eventually painting. Each discipline became a thread in a larger tapestry, allowing him to integrate his skills rather than choose between them. “Film is the perfect medium,” he reflects, “because through film I am a painter, a photographer, even a musician. It brings all of my multi-dimensional self into one harmony.”

Age and experience sharpened this perspective. As a younger man, Mukheli often felt pressured to choose one path, but maturity taught him that passions could coexist and even be monetised. He was encouraged early on to choose between being a photographer or director, but Mukheli was never one for binaries. Not only did he discover the effortless connection between his different pursuits, but the ways he could make a living from creating. “Growing older allowed me to understand that my passions can be monetised if I understand my relationship with them.”

His evolution was not only professional but deeply personal. Once hesitant to be photographed, shaped by ideas of masculinity and toughness, he now embraces archiving as a responsibility. When asked about why he once hated being photographed, he admits it stemmed from a fragile, unconscious idea of masculinity. “I just wanted to look tough,” he laughs softly. “I thought being photographed was boring… unmanly. My masculinity was shaped by the idea of me — the idea I thought people should think of me.”

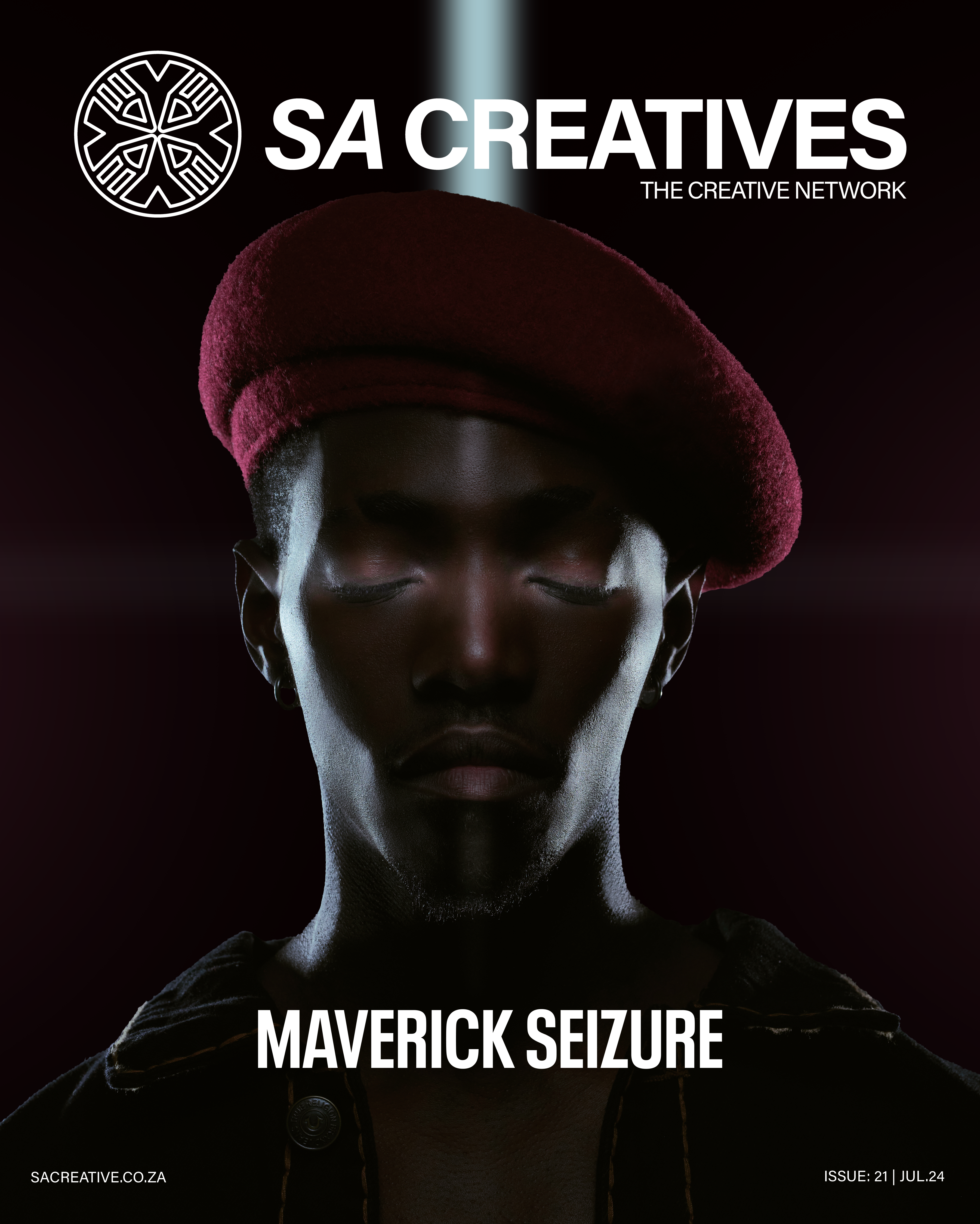

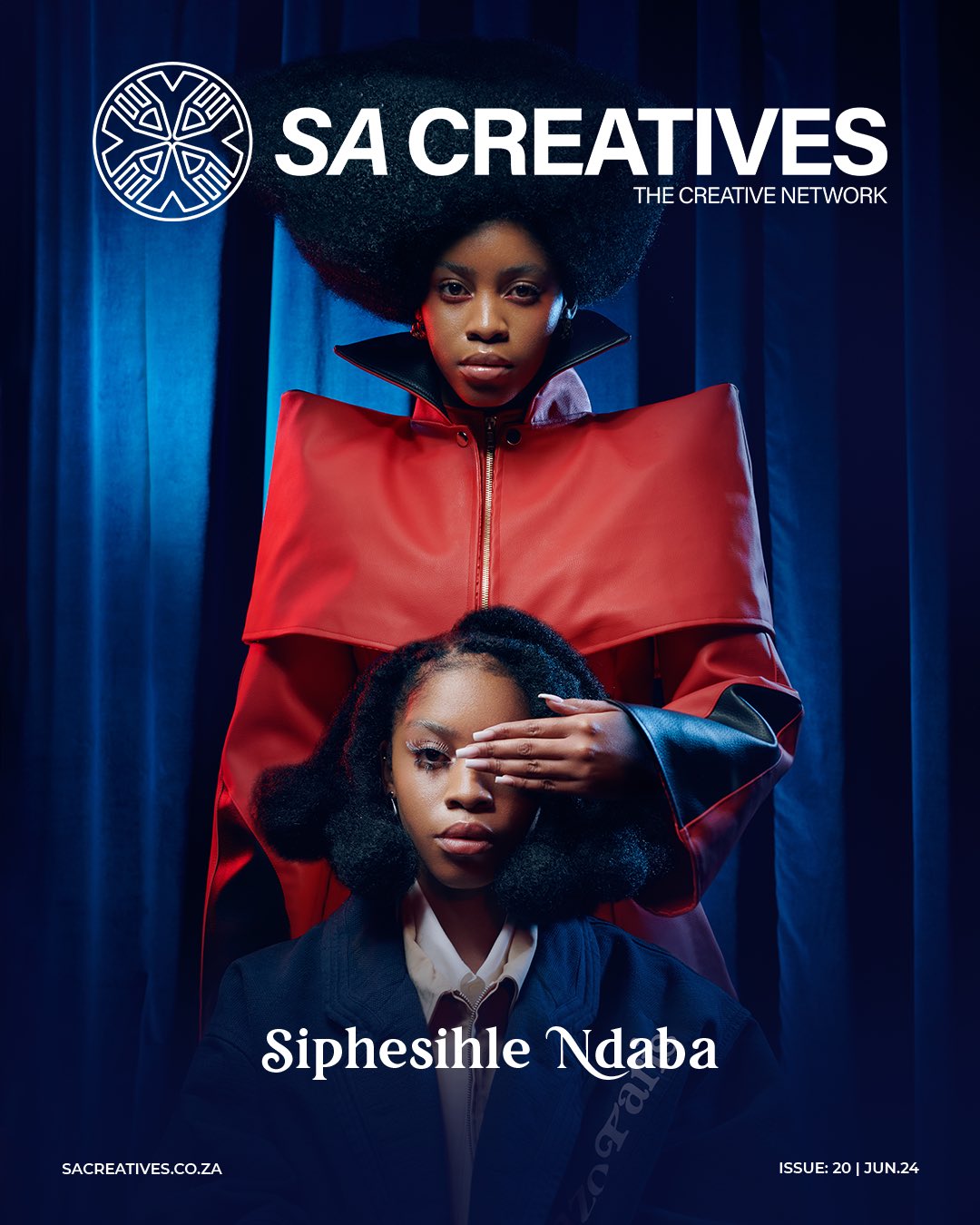

Despite this, Mukheli’s works highlight the beauty of blackness in the way he makes his subjects luminous and striking even in the most muted and simple shots. It is, of course, intentional, but more than that, the images and moments thereafter are intimate. “Portraiture is capturing someone’s essence,” he explains. “There’s a delicate space of trust between two people. You consider how the light falls on them and how your camera settings work in relation to the light in the space. Intimacy is a sensitive, delicate space of trust between photographer and subject, allowing you to capture their essence as they are. Sometimes we capture what we feel. I’ve worked with people when I was melancholic, and the photographs reflected that mood. They would say, “How were you able to photograph how I’m feeling?” Others have said my images resemble the way my presence makes them feel. Photography taught me stillness, intimacy, light, consent, and storytelling in a single frame.”

As a father, he further sees documentation as a gift to future generations, evidence of lived experience, a counter to the staged and incomplete archives of the past. “Our archive was not handled by us,” he says. “Now it’s my responsibility to create an authentic record for my daughter,” Yet, beyond his own legacy, he thinks back to his parents, “I would have loved to see my parents’ beautiful life when they were my age… the real version.” The birth of his daughter deepened this impulse. He speaks tenderly about imagining the day he’ll drive through the city with her and say, This is where I used to work. This is who I was. “Archiving is so important. It’s for her. For her to look back and say, ‘Dad used to dress so cool,’ or ‘How ridiculous was your outfit?’”

Fatherhood has brought him into new emotional territory. His short film Discover Yourself, created for TikTok, conceptualised while his wife was pregnant, became a doorway into imagining his future as a parent. “The script gave me an opportunity to imagine my life in 16 years with my daughter,” he says. He wrote from lived experience, his sister’s girlhood, his parents’ relationship, the intimacy and challenges of fatherhood. “It took me down future memory lane.”

Now, he’s entering a new phase as a painter, working on a deeply personal body of work exploring spirituality across African and Christian traditions. “The work itself is a question,” he says. Centred around the symbolism of water, he places himself at the heart of the inquiry. “I’m working with browns, greens, yellows… the emotions I feel when I go into the space of those questions. It’s tough, but it’s where I am.”